In the trenches

- Jan 1, 2018

- 6 min read

Cottonwood man recounts his brutal days in Korea

Denis Matthys (on left) rests with fellow soldier, Jesse Martinez, in front of the bunker, which is attached to trenches. Contributed photo

Six days after Denis Matthys graduated from high school in Marshall, he joined the Army. His older brother, who had already started farming with his father, had received his draft notice. It was decided that Denis would take his brother’s draft number and that would give his brother two more years before he could be called up again. When someone signs up to serve their country they are given a U.S. number; if drafted, it is a draft number. Matthys went to the draft board and took his brother’s draft number and bought his brother two years. Matthys had four brothers, and eventually four of the five brothers served in the armed forces.

The newly enlisted men, many of them still in their teens, congregated at the Atlantic Hotel in Marshall to board the Greyhound bus, which took them to the Twin Cities and on to Fort Sheriden, Ill. From there, Matthys went to Camp Forsyth in Kansas for basic training. He returned home for a 10-day furlough after basic training and then reported to Fort Lawton, Wash., where he was processed to go to Korea. From there, he was flown to Hokkaido, the northern most of the Japanese home islands. Matthys’ company was assigned to replace the 45th Infantry Division known as the Thunderbirds of the Oklahoma National Guard.

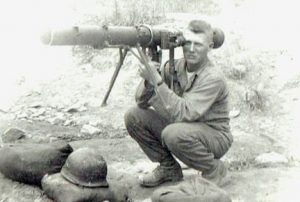

Denis Matthys aims a bazooka used during battle in Korea. Contributed photo

“The move to Korea was different from those of World War II. Companies were moved in to replace other outfits, so the Thunderbirds moved to someone else’s spot, and we took their place. To make this transition more effective, equipment was left behind, like weapons, armor, and vehicles. Unfortunately, equipment that was left behind was often faulty or just plain worn out. I ended up with an M-1 Garand rifle that was worn out, and at 200 yards, the bullets would tumble end over end. I complained and was told not to worry because most fighting took place at less than 100 yards, but I still worried.”

Eventually, he upgraded.

“Later, I picked up a riffle that a dead enemy soldier had, and it was one he had apparently gotten off of one of our guys,” he said. “It was just like brand new so I turned in the old gun and used the newer one from then until I went home. It was a nice gun, and I wanted to keep it but that wasn’t allowed.”

“Korea is a very hilly country with lots of ridges and rice paddies growing in the valleys,” he said.

But in November, the weather turned very cold.

“Most of the troops were from the upper midwest and were used to winter weather, but the troops from the southern states suffered due to the cold conditions. We dug our trenches by hand with small shovels and picks; it was very rocky ground. The trenches and fight positions were connected to the bunkers, which were holes in the ground covered with logs and sandbags and they did offer some relief from the weather.”

Matthys said many of the Korean troops got frostbite on their toes during this time.

“After about a month of the harsh weather we received special boots called Mickey Mouse boots because they looked so fat, but they kept our feet warm. It snowed there, but there was no wind, so the snow just lay where it fell with no drifts. When we got the boots we also got new sleeping bags that would open when you spread your arm instead of having zippers.”

Matthys said too many soldiers were shot or had been bayoneted because they couldn’t get out of their sleeping bags fast enough. The new sleeping bags helped this problem.

“We slept in our clothes but had to take the Mickey Mouse boots off; they were too bulky to fit in the sleeping bag. I always slept on my back with my arms and hands across my chest and my pistol in my hands,” he said. “We often went two months or more without a shower.”

Matthys and his fellow soldiers were on the MLR (main line of resistance), also known as the front line.

“Once in a while a priest would come through, and we all went to mass. There were no atheists in the trenches of Korea when fighting broke out,” he remembered. “When the battle was going full bore, there was cussing, swearing and praying all at the same time while guns jammed, soldiers were wounded, ammunition and grenades were running low, trenches caving in, and everything that could go wrong was going wrong.”

Matthys said days were less stressful than the night.

“The enemy would not fight in the daylight,” he said. “They liked the cover of night. When the mortar was flying at us we weren’t too worried, but when the shelling stopped, we knew they were slipping past our barbed wires and could be sneaking up on our foxhole. They were so quiet you never could hear them coming. It was always good to see dawn breaking because they backed off as soon as there was light, and we figured we would live for another day. In the 16 months I served in Korea we never fought one battle in daylight.”

Outpost Eerie was right in front of the company Matthys served in, Company K.

Denis Matthys stands by just a few of his war memorials in his home near Cottonwood. Photo by Ida Kesteloot

“We had 26 men in the company, and we were moved to Outpost Eerie for a five-day tour of duty. One evening, seven of us, including me, were assigned the job of guarding a bulldozer that was trying to bulldoze a road to the outpost. They were working at night by starlight. It was our job to keep the Chinese from attacking the bulldozer. Everything was quiet for about an hour and a half then they started hitting us with artillery and mortar, they then went after Eerie. After about four hours our company was ordered to go help those at Eerie, but by the time we got there, it had been overrun by the Chinese and just about everyone was wounded or dead. Our second in command, Lieutenant Manley, and another soldier were captured by the Chinese. One medic on Eerie was able to get four soldiers into a bunker and killed five Chinese who were trying to finish them off. One thing I never understood was the rule that medics were not supposed to be armed. They were supposed to be in the middle of it but not carry a weapon. Many did carry a pistol, and I would have, too.”

The 45th Division attacked and captured Pork Chop Hill, Old Baldy, and Outpost Snook and tried again to seize Outpost Eerie from the Chinese after they had taken it from our soldiers. To dislodge the Chinese 43,600 shells were thrown against the outpost plus 58 close support air missions were called in, according to Matthys.

Denis Matthys and others serving in Korea stop to pose for a picture. Contributed photo

“Even after the enemy had been forced off Eerie they launched four counterattacks but were unable to retake the hill,” he said. “The following morning after such a battle was something to behold. There were bodies lying all over, holes and craters everywhere. The hills of Korea were all covered with dense tree growth before battles took place, and after a battle, it looked as if everything had been burned off, that is how Old Baldy got its name.”

Eventually Matthys gained enough points to go home. There were a total of 429 combat days accumulated. The fighting continued for another year after he left Korea.

“I left Korea the same way I arrived – on a troop ship, and I will never forget the refugees standing aside with whatever they could carry on their backs hoping to get on the ship that was taking us away. Some 98,000 to 100,000 were taken by our country to the U.S. No other country would have shown such mercy to so many. It was incredible to see how poor they were,” said Matthys. “One man carried nothing but one wooden wheel. We kind of joked saying to each other. What will he do with one wheel?” While Matthys talked about his experiences it is plain to see the pain of losing so many fellow soldiers, young men like him who never made it to the next sunrise. An even stronger feeling you see in his eyes is the pride of serving his country.

Comments